Envisioning the Future of Cities Through Craft Beer — Practicing Transition Design 【Regenerative City Inspiration Talk Vol.7 — Part 1】

On November 19, the seventh session of the ongoing event series Regenerative City Inspiration Talk—Exploring the Future of Regenerative Cities from Tokyo was held at Tokyo Living Lab in Yaesu, Tokyo. This session focused on “Community Beer Project: Envisioning the Future of Regenerative Cities—Exploring Craft Beer Making Through a Transition Design Approach.”

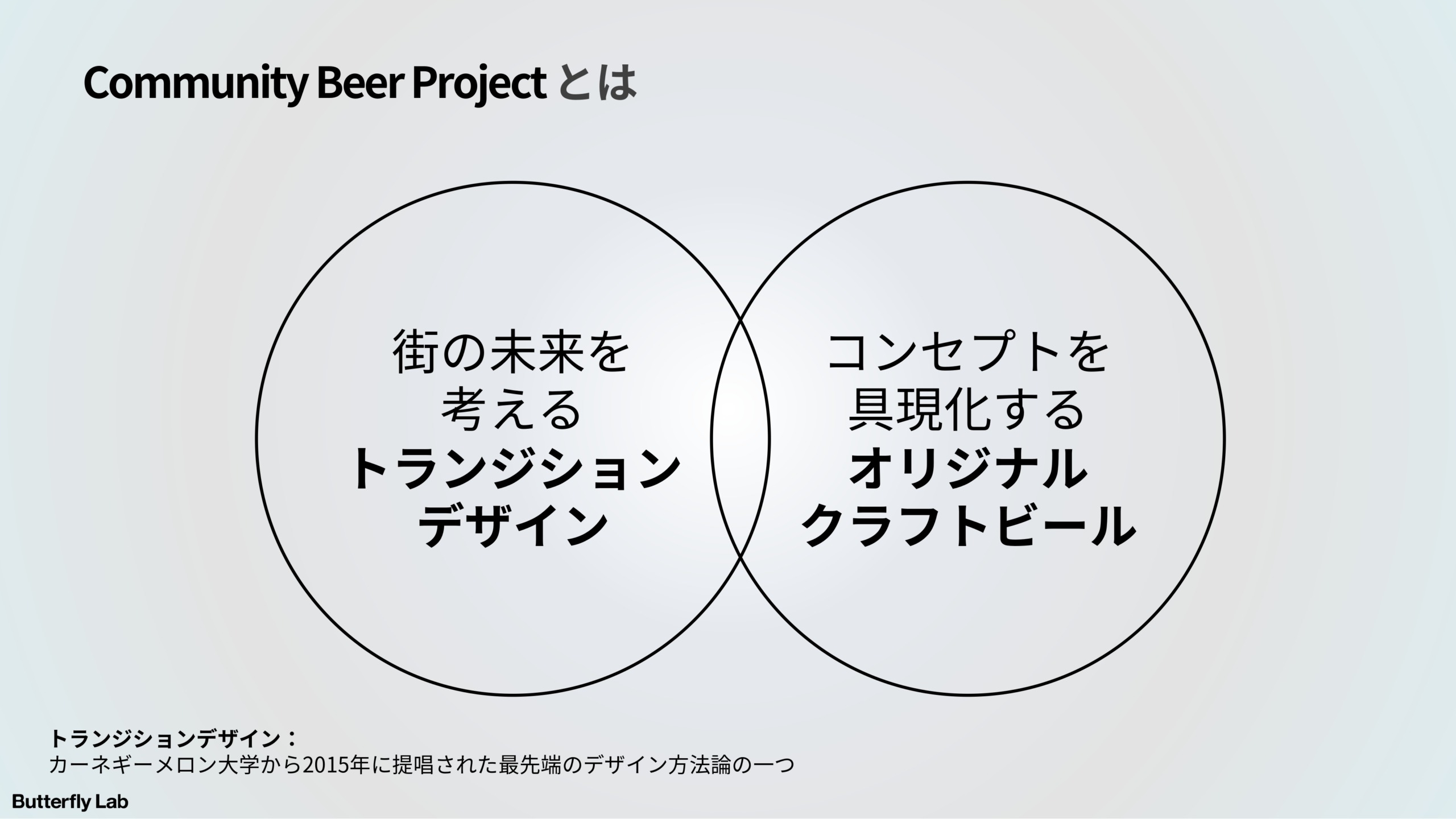

The Community Beer Project originated from RegenerAction Japan 2024, an international conference centered on regeneration. Set in the Yaesu, Nihonbashi, and Kyobashi (YNK) area, the project aims to create a community-based beer while fostering transformation within urban communities. By combining craft beer production with the principles of transition design—a methodology for designing social systems—the initiative explores new ways of catalyzing change at the community level.

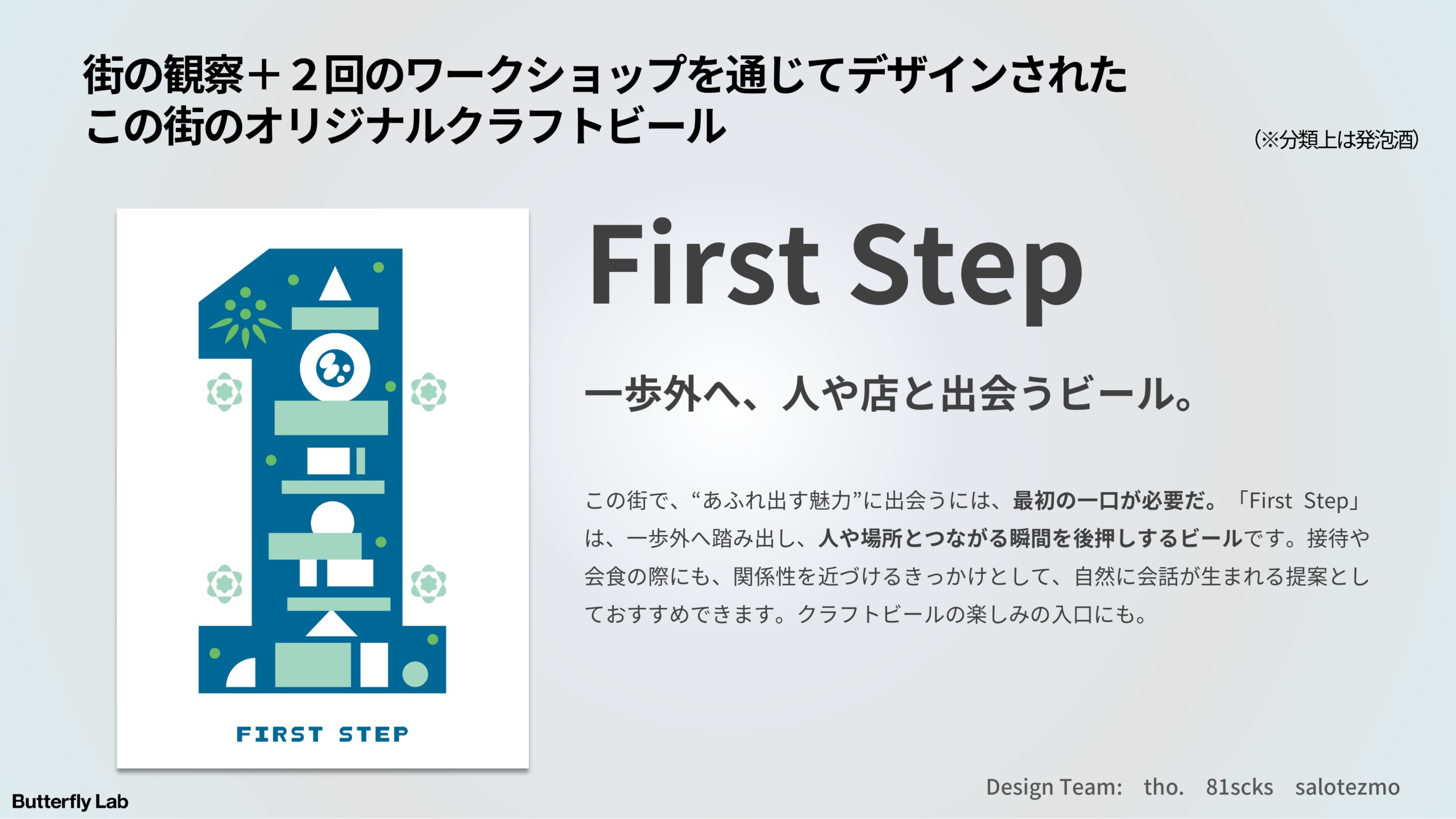

At the event, Daiki Matsumura, Representative Director and systemic designer at Butterfly Lab Inc., who led the project, and Daizo Matsubara, Representative Director of Zou Inc., who oversaw the creative direction, took the stage. Together, they reflected on the project’s journey while introducing the completed original brew, First Step.

Note: First Step is classified as happoshu (a low-malt alcoholic beverage) under Japanese law and is not legally categorized as beer.

“Cheers!”

The event began with a resounding toast led by Daiki Matsumura, who raised a glass of the freshly completed craft beer, First Step. Participants followed suit, taking generous sips of the beer in their hands. What quenched their thirst was a golden ale with a bright, light mouthfeel.

The beer was brewed with the cooperation of BALDYS, a local brewery based in Nihonbashi Kabutocho. At the venue, jumbo dumplings from Taikoro, a long-established Chinese restaurant in Yaesu with close ties to the brewery, were also served.

As participants savored the food and drink, Matsumura highlighted one of First Step’s most distinctive features: the use of a spice called aomoji as a secondary ingredient. Known as “makgwao” in China, where it is widely used, aomoji is relatively overlooked in Japan. Even when it grows wild in wooded areas, it is often discarded rather than utilized. Taizo Matsubara, who was responsible for the art direction of the Community Beer Project, went on to explain the reasoning behind choosing this ingredient and the intentions embedded in the can’s design.

“Aomoji has a strong, distinctive aroma, yet it has long remained something of an overlooked presence—despite its potential,” said Taizo Matsubara. “We felt that shining a light on such an ‘unsung’ ingredient resonates strongly with the regenerative context. True to its name, aomoji has bluish-toned wood and beautiful flowers, and we wanted to reflect those elements and stories in the design as well.

At the same time, as the name First Step suggests, our aim was not to create something that ends once it is made, but rather something that carries a sense of anticipation—a feeling that this is just the beginning, and that it will continue to grow and evolve from here.”

The aomoji used in the beer was sourced directly from Kagoshima through Japan Plant Research Institute, an organization that conducts on-the-ground research into mountain vegetation while exploring practical uses for native plants. By studying and utilizing forest ecosystems, the institute seeks to address the complex challenges facing Japan’s forestry industry, while also uncovering the potential of indigenous Japanese spices.

Although aomoji is known for its distinctive aroma, only 300 grams of the fruit were used in a 500-liter brewing tank. Matsumura explained, “Even when you lightly twist and crush the aomoji, it releases a rich, citrus-like fragrance. I hope people will first enjoy that aroma in their mouth—and then let this unusual yet memorable scent spark conversations, prompting reactions like, ‘What is this?’”

He expressed his hope that the beer would function as a medium for communication, bringing people into dialogue through shared sensory experience. Precisely because this was a one-time, single-batch craft beer, an “ichigo ichie”—a once-in-a-lifetime flavor—was born. In that fleeting taste, the essence of the project’s intention is distilled.

The origins of the Community Beer Project can be traced back to a workshop held at the international conference RegenerAction Japan 2024 in November 2024. The project began with a simple yet fundamental question posed during a brainstorming session: “How can we regenerate urban communities?”

Building on the discussions that emerged from that workshop, Matsumura outlined three underlying hypotheses that shaped the project’s core perspective.

First, urban life that becomes increasingly draining the longer one lives there:

He questioned whether the relationship between the city and its residents has become net-negative overall.

Second, a lack of attachment and loyalty to the city:

Has the city become merely a place of convenience or a destination to serve specific purposes?

Third, the thinning of human connections and shared experiences.:

Have we fallen into a mindset of instrumentalism—viewing everything solely as a means to an end?

These issues resonated with reflections shared at the event by its moderator, Motohiro Taniguchi of Tokyo Tatemono Co., Ltd.. “I had worked in Yaesu for about seven years at that point,” he admitted, “but to be honest, my attachment to the area was minimal—it was simply where my company happened to be located.”

In response, Matsumura suggested that this lack of emotional connection stems from viewing the city not as a destination in itself, but merely as a means—for commuting, shopping, or fulfilling practical needs.

To address these fundamental challenges, the project adopted an approach known as transition design. This framework expands the scope of design beyond traditional graphics or products to encompass user experiences, culture, and even entire social systems. With a long-term perspective, transition design seeks to intentionally shape societal transitions toward more sustainable and regenerative futures.

Explaining why transition design was paired with craft beer, Matsumura pointed to the inherent sense of inclusiveness that craft beer offers. Its flexibility allows it to incorporate a wide range of secondary ingredients—from local agricultural products to surplus or rescued food materials. At the same time, unlike wine, it does not demand specialized or rigid knowledge, making it approachable and easy to enjoy without pretense.

It was precisely these qualities, he explained, that led him to see craft beer as an ideal medium for building urban communities—a form that invites participation, lowers barriers, and naturally brings people together.

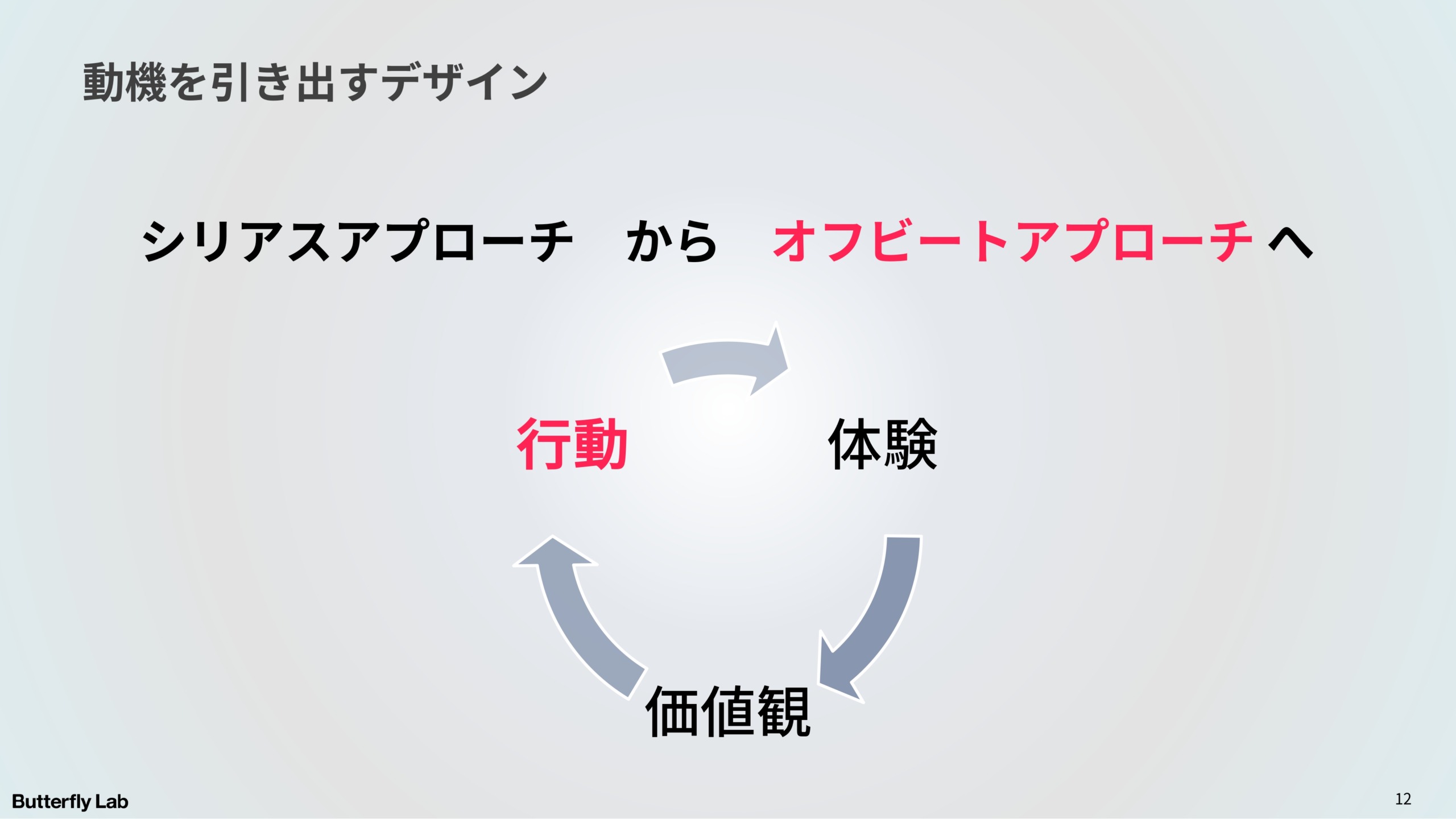

Equally important is the project’s adoption of what Matsumura describes as an “offbeat approach”—a methodology that deliberately avoids overly serious or formal entry points.

“If we start with a heavy, earnest message like ‘Let’s seriously think about the future of the city,’ it becomes difficult for people to engage,” Matsumura explained. “Instead, we intentionally kept the entry point casual, inviting people with the simple idea of ‘Let’s make craft beer together.’ That lightness helps draw people in naturally.

Within the process of making craft beer, however, we embedded mechanisms that encourage participants to think deeply about the city’s history and its future. What begins as something approachable and enjoyable gradually opens the door to much deeper reflection.”

Taniguchi also reflected on the contrast with conventional development work. “In typical development projects, there are clear pressures—defined goals, deadlines, and expectations,” he said. “In this project, however, there was a sense of space and ambiguity. I believe it was precisely that openness that allowed so many people to become involved.”

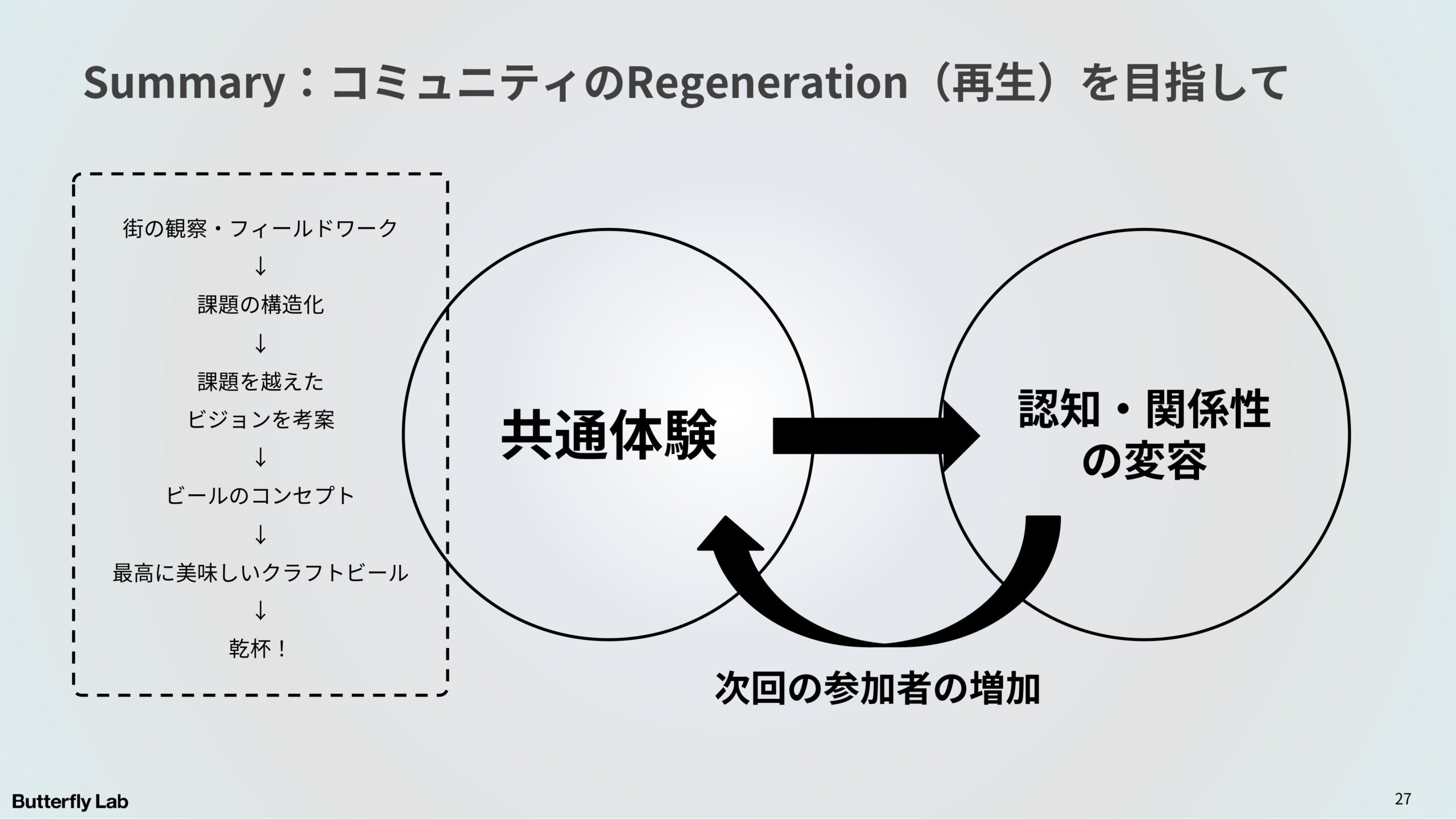

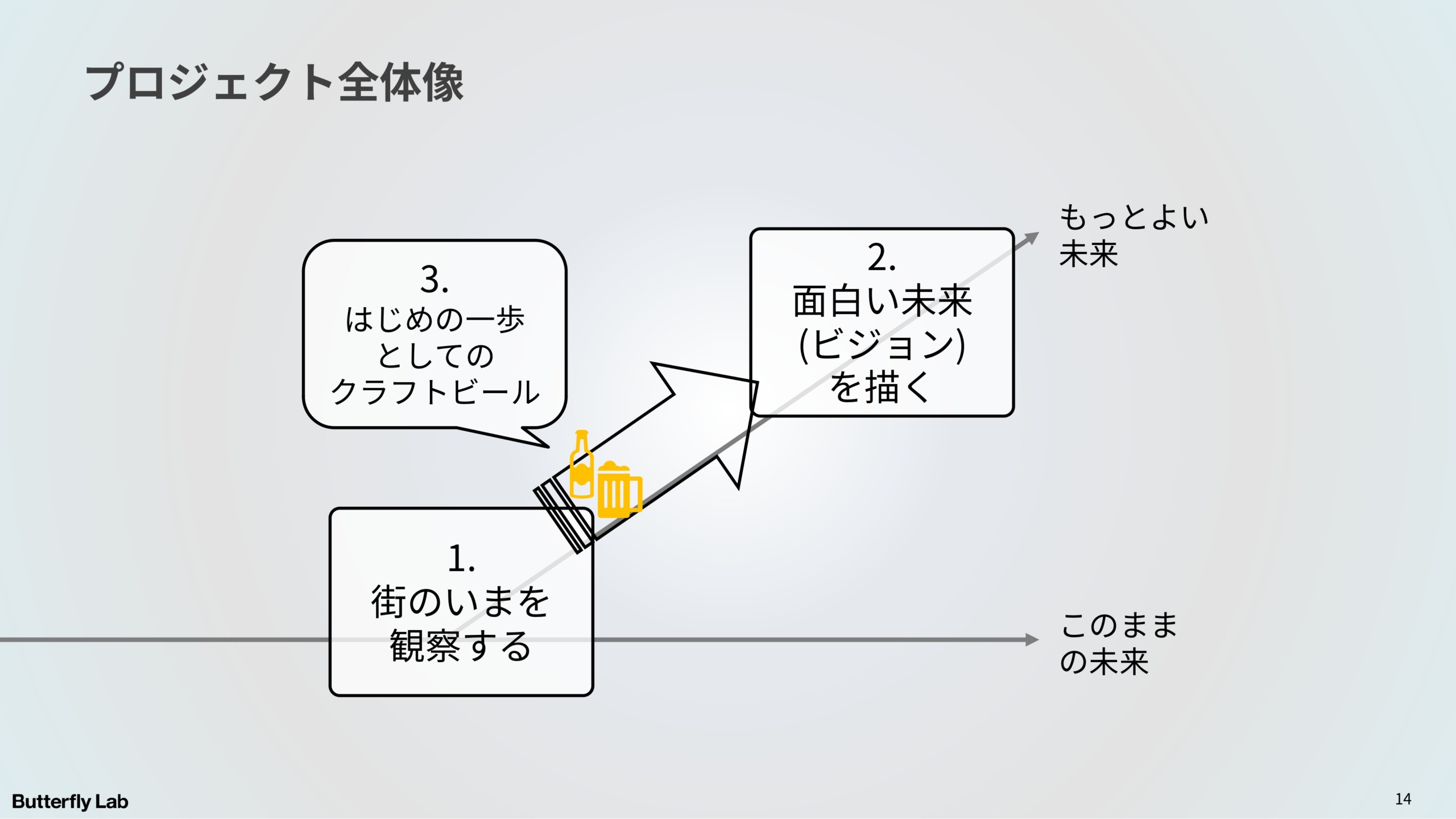

The project was guided by a design framework that combines transition design with theories of behavioral change. This process was broadly divided into the following three steps.

①Observe the City as It Is Today

②Envision an Engaging Future (Vision)

③Craft Beer as the First Step

This approach begins by acknowledging the “default future”—the predetermined trajectory that lies along an extension of current conditions—and then intentionally designing a transition toward a better possible future that branches off from it. While the framework combining transition design and behavioral change theory originally consists of five steps, this project focused on the first three steps as a practical entry point into social transformation, using craft beer making as the medium.

The process began with fieldwork designed to physically experience the city as it is today. Project participants gathered at a long-established public bathhouse in Ginza before heading out into the surrounding streets. As they walked through the area, they observed and photographed both the city’s “interesting elements” and its “disappointing aspects.” Observations such as “the tree-lined streets disappear when moving from Ginza into Kyobashi,” “there are grassroots efforts to create green spaces in the gaps between buildings,” and “the separation of pedestrians and vehicles makes the area clean and safe” were shared, written down, and posted on the walls.

What mattered most was not simply listing these observations, but structuring the challenges by drawing connections between them. Participants collectively unraveled loop structures in which a single phenomenon could lead to both positive and negative outcomes, or where one factor ultimately reinforced the original problem. This shared process of mapping relationships helped reveal the deeper structure of the city’s challenges.

The project progressed through two such workshops, along with additional discussions to determine the beer’s secondary ingredients. However, the process was not without friction. During the first workshop, representatives from long-established local restaurants voiced tough questions, asking, “Does this neighborhood really need craft beer in the first place?” Because craft beer is often associated with bold, highly distinctive flavors, chefs were understandably concerned about whether a beer could be created that would truly complement their cuisine—and whether the project would take that level of consideration seriously. Matsubara later reflected that this workshop left the strongest impression on him.

“In the YNK area, which is also known as a district of fine dining, beer is not meant to be the star,” Matsubara explained. “It exists as a supporting presence—something that enhances the meal and fits within a broader culinary context. Precisely because of that strong feedback, we were able to define the direction of a beer that wasn’t just bold in flavor, but one that this neighborhood genuinely needed.”

Through these earnest discussions, what gradually came into focus was the dilemma facing the neighborhood—in other words, its underlying system structure. Matsumura defined that structure as follows.

“The greatest appeal of the YNK area, which has served as a hub for transportation and commerce since the Edo period, lies in the stories of the people who have carried that legacy forward,” Matsumura explained. “However, precisely because it is such a key location, large-scale developments prioritizing convenience and efficiency have advanced. As a result, the city has been neatly segmented—above ground and below ground, buildings and shops clearly separated.

People now move along the shortest possible routes, chance encounters have diminished, and opportunities to come across the human stories that should be at the heart of the area’s appeal have decreased. We hypothesized that this has created a loop structure that gradually pushes people further apart.”

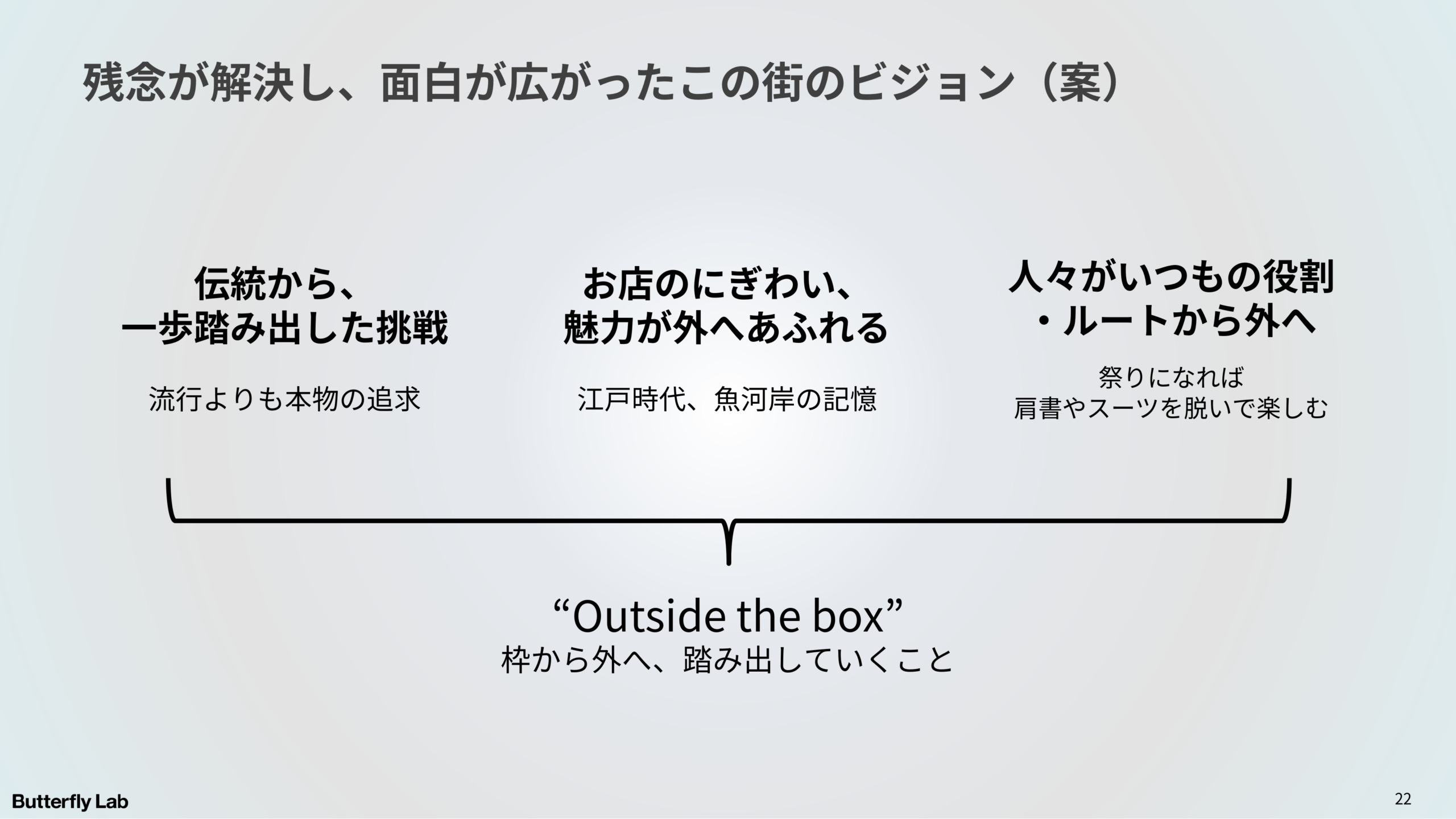

As a vision for breaking this loop and allowing the city’s appeal to spill outward, Matsumura proposed the concept of “Outside the box.” Observing how long-established businesses have continued to take on new challenges with each successive generation, he reframed the area’s true strength as not merely preserving tradition, but stepping beyond established boundaries.

Under this vision, the liveliness and aromas of shops spill out beyond their noren curtains, creating moments that encourage people to step outside their usual roles—whether as “office workers” or “shop owners”—and even outside their habitual commuting routes. The name given to the finished beer, First Step, embodies this very aspiration: an invitation to take that first step beyond the familiar.

Through fieldwork and workshops grounded in transition design, this project revealed the underlying system structures shaping the city and articulated a shared vision of “Outside the box”—stepping beyond established frames. In Part 2, we will explore how the completed craft beer, First Step, begins to function as a “seed” within the city, as well as the ideas participants shared around what they envision as the “Second Step.”

(Text by Michi Sugawara / Photographs by Shuji Goto)

Butterfly Lab Inc.

After working at Yahoo Japan on business development and branding with U.S.-based companies, as well as post-disaster reconstruction support following the Great East Japan Earthquake, Matsumura founded Harmonia Inc. in 2015. He has since led initiatives focused on food loss reduction, corporate consulting, and vision-making.

From 2025 onward, under the name Butterfly Lab, he has been engaged in collaborative exploration projects that address complex challenges such as climate change, the future of cities, and industrial transition—approaching them through the lenses of behavioral change design and transition design. He has a deep affection for craft beer, bookstores, and public bathhouses. His publications include The New Textbook of Pricing: From the Fundamentals of Price Setting to the Frontlines of PriceTech (Diamond Publishing).

Zou Inc.

Matsubara began his career as a spatial designer, working on a wide range of projects including offices, factories, schools, and hotels. In 2024, he founded Zou as a human-centered design management company, aiming to create comfortable and meaningful transformation for organizations, businesses, and individuals—starting from the design of places where people work.

In parallel, he serves as a brand manager at Regale Inc., operating food and beverage establishments rooted in Asakusa and loved by the local community—or aspiring to be. Through these activities, he is also deeply committed to community design.